San Benito Vineyards and Wine - April 2025

“Off the beaten path”

Nearly every article I’ve read about the wineries and vineyards of San Benito County includes this phrase, and for the wine daytrip I’d planned to the region, it certainly seemed apt. I’d visited Siletto Family Vineyards in San Benito with friends last year, but they’re just off the main highway through the county – that was not the case with this year’s destinations. I was joined on this trip by friends Wes, Stephanie, and Larry, and planned three visits for the day, all of them highlighting different aspects of what’s going on in the San Benito County wine world.

It was a cool and overcast Friday morning as we all joined up in Mountain View. I offered to drive, while Stephanie let us use her car since it was larger and would accommodate the four of us more easily. After driving south past San Jose and Gilroy along Highway 101, we turned east and proceeded to the town of San Juan Bautista, where we stopped for a driving break and (very good) coffee at Vertigo Coffee Roasters. The coffee company name is a nod to the classic Alfred Hitchcock movie that used Mission San Juan Bautista in key scenes. Continuing from there along a series of small side roads southeast of town, we came to our first wine destination of the day.

Before proceeding further, it might be useful to provide a brief introduction to San Benito County and its place in California wine history.

Introduction to San Benito County

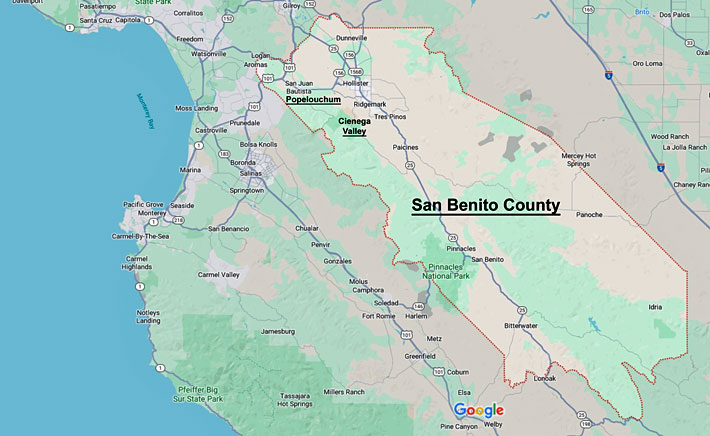

The vineyards of San Benito County include some of the older plantings in California, yet they’re not very well-known, even among many fans of California wine. The region is located south of Santa Clara Valley and east of Monterey County, between the Gabilan and Diablo mountain ranges. It’s generally warm during the summer, though afternoon maritime breezes coming down from Monterey Bay and through the Hollister area help to temper the heat. Historically, agriculture and mining (mainly for quicksilver) have been important to the county’s economy, though mining operations have fallen off over the years. The region includes two major earthquake faults – the San Andreas and Calaveras faults run through the county, contributing to its interesting geology and mix of rock and soil types, including volcanics, decomposed granite, and limestone, as well as some rare minerals.

The first commercial winegrape plantings in San Benito County came around 1851, when Frenchman Theophile Vaché planted vines in Cienega Valley, at what are now DeRose and Eden Rift vineyards. William Palmtag purchased Vaché’s vineyard in 1883 and expanded it, adding more grape varieties. It’s been said that some vines planted in the mid-1850s remain at DeRose. Enz Vineyard, in the same area, may have first been planted as early as the 1880s, and some of those vines are still producing. Other vineyards that were initially planted by the early 1900s include Wirz and Gimelli (formerly El Gabilan). Wirz also has Riesling vines dating to the 1960s. Josh Jensen began planting his Calera vineyards in the Mount Harlan area in 1974. San Benito County’s vineyard heyday came in the 1970s when wine giant Almaden had extensive vineyards in the area. But that era didn’t last long for the region, and many of those vineyards are gone now. Newer plantings of note in the past 30-40 years include Siletto Family Vineyards, Vista Verde, and Paicines Ranch.

San Benito County includes five AVAs entirely within the county borders: Cienega Valley (1982), Lime Kiln Valley 1982), Paicines (1982), San Benito (1987), and Mount Harlan (1990). There are also three AVAs that are partially within San Benito County, including their most recent one, Gabilan Mountains (2022).

In the past ten years or so, a number of smaller-scale vintners have discovered the vineyards of San Benito County and have sought out fruit from there, particularly older plantings of varieties such as Négrette and Cabernet Pfeffer, which may not be grown anywhere else in California. And the newer vineyards in particular have planted or grafted many varieties originally from Italy, Spain, Greece, France, and elsewhere in Europe that are little-known in California vineyards. Nearly all of these vintners make their wines outside of San Benito County, and there are still very few wineries within the county itself.

Popelouchum Vineyard

The first stop of our San Benito County wine tour was a short drive from the town of San Juan Bautista, meeting with Randall Grahm at his Popelouchum Vineyard. It’s a little tricky to find, but Randall had given me great directions in advance and then called me as we were about to enter the vineyard to let us know how to get to where he was. Once we found the right spot and parked, Wes, Stephanie, Larry, and I got out of the car and Randall welcomed us to the vineyard. Randall is one of California’s most legendary vintners, and he has a long history of being something of an iconoclast in the California wine world, so it’s no surprise that his current vineyard reflects that iconoclastic nature.

Randall was born and grew up in the Los Angeles area. He studied philosophy at UC Santa Cruz before returning to Southern California and taking a job at a wine shop, where he first experienced some of Europe’s great wines. He was especially enamored of Burgundy and began to think of making Pinot Noir in California. He enrolled at UC Davis and earned a degree there in 1979, and while there, he also visited Berkeley, where he discovered Kermit Lynch’s wine shop and tasted more wines from the Rhône and other French wine regions. By this time he was a firm believer in terroir and its key role in wine.

Not long after this, Randall was able to purchase property just outside of the tiny Santa Cruz Mountains hamlet of Bonny Doon, only a few miles from the Pacific Ocean. He planted mostly Chardonnay and Pinot Noir at this site, but he was disappointed with these wines and as early as 1983 he began to look at non-Burgundian grape varieties as an alternative. He purchased Syrah fruit that year, and the following year he also bought Grenache and Mourvèdre to make a California rendition of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, and voilà! Randall made his first “Le Cigare Volant” southern Rhône-style blend in 1984. One of the state’s original “Rhône Rangers,” he’s received numerous honors since then.

In the following years of Randall’s Bonny Doon wine label, he produced wines from a broad spectrum of grape varieties, some fairly common in California but many that were (and still are) considered esoteric varieties here. Production of the wines took off, and Randall spun off related labels such as “Big House Red,” “Ca' del Solo,” “Cardinal Zin,” and “Pacific Rim.” As has been the case with a number of vintners whose production increases dramatically, he felt he was getting farther from what he loved doing, and he sold off his labels starting in the early 2010s, eventually selling the core Bonny Doon label at the beginning of 2020.

Randall could easily have enjoyed a relaxing retirement, but resting on his laurels would not have been his style. All through his wine career he’s looked for something new and different, whether it was unusual (for California) grape varieties, uncommon winemaking techniques, humorous labels that tell an interesting story, and the like. Though he certainly still pursues these facets of wine, in the past ten years or so he’s focused more on how grapevines are grown and propagated – working with distinctive methods of tweaking existing varieties and of creating new ones. This brings us to Randall’s Popelouchum project.

Popelouchum (pronounced pope-loh-SHOOM) comes from the name that the Native American Mutsun tribe gave to their land, and it’s also supposed to be word for “paradise” in their language. Randall purchased the vineyard property in 2012, and one edge of the site is right on the San Andreas Fault. The entire property is a little over 400 acres, and extends up and just over the hills to the southwest of where about 18 acres are currently planted. The climate at the vineyard site is relatively cool, and Randall compared it to the far northern part of Salinas Valley near the town of Chualar, where it’s cool and windy. Randall noted that the fruit from Popelouchum Vineyard tends to be particularly high in acidity, and the windy site may be a factor in this. The vineyard has a variety of soil types, including volcanic, granitic, and calcareous soil. The site doesn’t receive a lot of rainfall, and Randall said there’s not great access to water at the site as there’s no real aquifer below. The established vines do need some irrigation but Randall said it’s typically only once or twice in a growing season. In addition to the grapevines, he also grows olives, pears, apples, quince, and fava among other plants in order to foster biodiversity. Randall told us that he particularly loves quince, and said he wants to “make the world safe for quince!”

Grape varieties currently planted at Popelouchum include Grenache Blanc, Grenache Gris, Grenache Noir, Pinot Noir, Cinsaut, Ruchè, Roussanne, and Furmint. There are also self-crossed variants of Tibouren and both white and red self-crossed variants of Sérine (more on that later) plus “proper” plantings of Tibouren and Sérine. More varieties to be added include Cornalin, Nebbiolo Rosé, Schioppettino, Rossese Bianco, Timorasso, and Aligoté. These are particular favorite varieties of Randall’s and several of them are almost unknown elsewhere in California. The vines are farmed organically although the vineyard is not yet certified organic. There are cover crops planted between vine rows as well as native vegetation. Biochar produced at the site is added to the soil to help promote soil and plant health.

Randall talked with us about how his current projects can’t be fully figured out in advance, that it will be a process of experimentation to see what works and what doesn’t. For example, he loves sweet wines and has made a number of them in the past, and he wanted to make a botrytis-affected wine. He planted Furmint – the grape variety of Hungary’s renowned Tokaji Aszú sweet wines – around the vineyard pond near the low point of the property, hoping to help induce botrytis by the proximity, but it wasn’t working. So he grafted the Furmint vines to Petit Manseng but quickly found that he didn’t like the wine from it at this site – it was too acidic. The most recent development is that Randall had the Petit Manseng vines “decapitated” – he showed us where the earlier grafts were located near the base of the vines, and he’s hoping to promote sucker growth below the grafts to regrow the Furmint.

From the (hopefully) regrowing Furmint, we walked a short distance to rows of cordon-pruned Sérine vines, and Randall immediately began going vine by vine to clean up the early spring growth – and he soon had Stephanie’s assistance! Sérine is a variant of Syrah that originated in the Northern Rhône appellations of Côte-Rôtie and Hermitage. It has been shown to be genetically identical to Syrah, and though some believe that it’s a distinct clone of the variety, Randall has been told that it’s a virused strain of Syrah and he feels that this is most likely the case. Sérine can create a distinctive wine, different from that made from the typical Syrah clones. These vines are some of the “proper” Sérine plantings, as opposed to the self-crossed Sérine plantings elsewhere at the site.

Producing self-crossed variants of Sérine, along with ones from a couple of other varieties, is one of Randall’s main projects at Popelouchum Vineyard. The aim is to produce new variants that will be different than the parent vine. Randall told us that his self-crossed Sérine has produced both red and white variants, due to the genetic parents of Syrah being Dureza (red) and Mondeuse Blanche (white), with the recessive white characteristic appearing in about 25% of the variants. The self-crossing method produces seeds that grow into seedling vines, which in time can then grafted to rootstock to be planted in the vineyard. Randall said that the variants produced in this way have been very inconsistent, and a fair number of them have not been usable at all, but this was not unexpected. Interestingly, Randall told us that any virus from the original vines is not passed along in the seeds produced from self-crossing. He feels that fruit from the whites has been particularly promising so far, with some displaying peachy character and others more peppery.

Randall has propagated 65 white Sérine variants that he had planted in 2023 and he’s recently done the same with about 65 red variants. His thought is that rather than trying to identify a single “best” variant, the combination of many of them in a field blend may result in a more interesting wine and will better express his vineyard’s terroir. Randall told us that vines grown from seeds using this self-crossing method take longer to become productive, so it’s taking awhile for this project to (literally) bear fruit. It will take another two or three years to compare wine from the self-crossed red Sérine variants to that from the basic Sérine planting. It’s planned that the self-crossed Tibouren will also be planted soon.

Another experiment that Randall is working on is crossing Ciliegiolo and Picolit – an Italian red and white – to create new varieties. He’s stated that his goal is to create 10,000 new grape varieties from this, although he knows that in reality the number will be far less. The result of the Ciliegiolo and Picolit crosses is expected produce an assortment of different varieties. Randall plans to have the mixed offspring vines planted in each of the site’s three distinct soil types – volcanic, granitic, and calcareous – to see how the vines respond to that and how the fruit may express the different soil conditions.

Randall wanted to show us another part of his vineyard, so we got back in the car and followed him to a spot where he led us to head-trained Grenache Noir, Tibouren, Ruchè, and Sérine vines. He told us that he loves the three-dimensional nature of head-trained vines compared with trellised vines. In addition to Grenache Noir, the Grenache Gris and Blanc are also head-trained. Randall said that turkeys especially like the Grenache Gris fruit, and since the “Popelouchum Blanc” bottling is a blend of Grenache Blanc and Gris, the turkeys have a big hand in determining the proportion of each in the blend! In addition to turkeys, other birds, gophers and ground squirrels, and – surprisingly – coyotes have been particular vineyard pests.

After looking at some of the head-trained vines, we continued in our cars to the vineyard barn up the hill. There we saw both vine cuttings being propagated from a number of varieties (Sérine, Aligoté, Timorasso, and more) and young seedling vines in planters that had been repurposed from old grape harvest macrobins. Randall led us to a picnic table under a tree and set out four wines that he’d brought for us to taste.

The white Popelouchum wines are usually made with direct press and no skin contact, though there have been exceptions to that. They’ve been fermented and aged in neutral French oak barrels. Randall likes to ferment his red wines with a percentage of whole clusters, and uses the labor-intensive “passerillage” method of carefully air-drying these clusters for three or four days after harvest, to lignify the stems in order to avoid a “stemmy” character and to manage the tannins. Most reds get from 50% to 100% whole-cluster fermentation, and recent Pinot Noirs have been 100% whole-cluster. All of the wines are fermented with indigenous yeast, they all go completely through malolactic fermentation so they can be bottled without filtration, and they’re aged in neutral French oak. Because the wines are fairly high in acidity, they require lower levels of SO2 to keep them stable and free of spoilage microbes. The wines are made at Chualar Canyon Winery in Salinas, and they’re all bottled under screwcap.

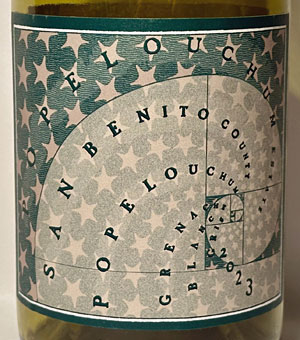

We started out with the 2021 “Popelouchum Blanc” – this is a blend of about 50% each Grenache Blanc and Grenache Gris, direct-pressed and co-fermented in neutral oak. This had subtle aromas of pear and stone fruit as well as saline and umami notes, with vibrant acidity and a persistent finish. We followed this with the 2022 “Popelouchum Blanc.” The blend is similar for this vintage of the wine, though the fruit came in somewhat riper than the 2021. Randall decided to give the fruit two hours of skin contact prior to pressing for this vintage. Showing a more upfront ripe stone fruit profile, this also had touches of spice, with a richer texture. Randall poured us one more white wine, the 2023 “Popelouchum Blanc,” which is about 60% Grenache Blanc and 40% Grenache Gris – the vineyard turkeys must have gotten to more of the Grenache Gris fruit that year! From this very cool and late-ripening vintage, the blend is back to a lower alcohol level (about 13% in this case) and like the 2021 wine it was direct-pressed with no skin contact. My favorite of the three vintages, the 2023 was somewhat reductive at first (it wasn’t racked until just before bottling) but opened up to display bright citrus and pear aromas along with savory herbal notes, and combining medium body with vibrant acidity and a long, lively finish.

As we were tasting the white wines, Randall got up from the table and told us that he wanted to see if he had a bottle of another wine in the small cellar at the vineyard barn, and he returned a short time later with an unlabeled bottle. This was the 2024 Tibouren Rosé – it has not been commercially released, as Randall was able to make only about two cases of this wine in 2024! Randall feels that Tibouren is better-suited as a variety for rosé wine rather than red, and he plans to make more Tibouren Rosé going forward. Wow - this wine was a stunner! Herbal and umami-forward plus subtle strawberry and floral components as well as a saline note, with bright acidity and a long fresh finish. Hard to put into words adequately but I think everyone felt that this was our wine of the day. We finished up with the 2022 Cinsaut “En Passerillage.” Randall told us that Cinsaut is one of his favorite red varieties. The fruit was whole-cluster fermented after air-drying for four days, aged in neutral oak, and is only 12% alcohol. This was more fruit-forward, featuring plum and black cherry aromas as well as floral and earth notes, with medium-light body, lively acidity, and moderate tannins.

Subsequent to our vineyard visit, I was able to attend a small gathering for a tasting and conversation with Randall at Wine on Piedmont wine shop in Oakland. He poured a few wines that we didn’t taste with him at the vineyard, and I was able to re-taste some of the wines we did try there as well. We started out with an unreleased NV Sparkling Grenache Blanc / Grenache Gris. This was a blend from the 2018 and 2019 vintages, with extended aging in puncheon and then in bottle. Zippy acidity, with subtle aromas of ripe apple, apple skin, and herbs, with fine bubbles and a lingering finish. Randall also poured two vintages of Popelouchum Pinot Noir – there are twelve Pinot clones densely planted in a higher-elevation north-facing vineyard block. First was the 2022 “20.000 pieds/ha” Pinot Noir, with floral red fruit, fresh herbs, medium body and lively acidity – this seems like if could use more time to develop. The 2023 “Exuberance” Pinot Noir is already beautiful, with very floral aromatics, cranberry and strawberry fruit, a savory component, a bit lighter weight than the 2022 with great acidity and a vibrant finish.

Randall is hoping that he’ll be able to get the first commercial harvest of Tibouren, Ruchè, and “Sérine Blanche” this year. The first commercial wines from the vineyard were from the 2020 vintage. Current production is small, less than 1,000 cases, but Randall hopes that it can grow to around 5,000 cases after more vines are planted and start to produce fruit. Opening a tasting room may be in the future, though that does not yet seem imminent. Another possible future development is having a separate AVA approved for the area around Popelouchum, though this is also probably still a ways off.

I should mention Randall’s other wine project here. The Language of Yes focuses on wines from Rhône and southwestern French grape varieties, all sourced from Central Coast vineyard sites. Randall is partnering with Gallo’s Luxury Wine Group on this label. I tasted a few of The Language of Yes wines last summer and was impressed. The 2023 “Les Fruits Rouges” Rosé was made from mostly Grenache and Cinsault plus a little Tibouren, while the 2022 “En Passerillage” Grenache and 2022 “En Passerillage” Syrah, both sourced from cool-climate Rancho Réal Vineyard in Santa Maria Valley, each use the same process of air-drying grape clusters as the Popelouchum wines. For fans of Randall’s wines, The Language of Yes is another label to look for.

This was a memorable visit with Randall at Popelouchum Vineyard. I was very impressed that he’s continuing his search for terroir in California and is in the midst of several fascinating projects that push the envelope for how grapevines are propagated and grown here. Randall was a wonderful host at the vineyard – I certainly learned a lot there, and he kept us all very entertained as well. I really enjoyed all of the wines we tasted, and my favorites were the 2023 “Popelouchum Blanc,” 2024 Tibouren Rosé, and 2023 “Exuberance” Pinot Noir, while the 2021 “Popelouchum Blanc” and 2022 Cinsaut “En Passerillage” were not far behind. Though it’s still too early to tell just how Randall’s current work at the vineyard will turn out, we should start to see some results in the next few years. But as evidenced by the wines already being made from there, it’s certainly not too early to enjoy the wines of Popelouchum Vineyard.

DeRose Winery

We drove from San Juan Bautista up into the Gabilan Mountains along Cienega Road, and arrived at our next San Benito County wine destination, DeRose Winery in Cienega Valley. I actually drove right by the winery, as the signage outside is unobtrusive, but we quickly doubled back and parked across the road from the older wood buildings. Wes, Stephanie, Larry and I walked in from the road, and we soon met winemaker Alphonse “Al” DeRose working inside. I’d been in contact with Al about our visit, and though he’d been busy preparing for bottling wine the following week, it turned out to be a good time for him to take a break from that and pour some wines for us to taste. He led us into the large barrel and tank room of the winery, where a long tasting counter is set up along one side – a wonderfully old-time tasting set-up that seems a nod to California wine heritage. The large and utilitarian winery buildings date from the early 1960s when Almaden Vineyards owned the property. Remarkably, a trace of the San Andreas Fault runs right through one of the buildings – though fortunately not the one where the tasting area is located!

Al talked with us about the winery and vineyard as we began our tasting. DeRose is particularly historic – wine production there (under various owners over the years) has been going on continuously for over 170 years, said to be the longest ongoing wine production in California. Frenchman Theophile Vaché planted the first grapevines at the property around 1851. He was selling wine from his vineyard by 1854, and Al told us that they have documentation of Négrette plantings there as far back as 1855. The property went through a number of owners in subsequent years – William Palmtag and John Dickinson produced award-winning wines there and both of them enlarged the vineyards in the later 1800s and early 1900s. The winery produced sacramental wine to keep the business going during the Prohibition years, and the Valliant family ran it for some time. In 1953 Almaden bought the land, later selling it to Heublein in the mid-1980s, and vineyard health and wine quality suffered during this period of large corporate ownership. After splitting the large property into two and selling both parts in 1988, one part became Pietra Santa Winery (now Eden Rift), while the DeRose and Cedolini families purchased the other part, which became DeRose Winery.

The DeRose family has deep California farming roots. The family, including Al’s father Pat, his grandfather Gene, and great-grandfather Francisco, grew prunes, cherries, and apricots on a 60-acre ranch in San Jose’s Willow Glen area from about 1930 to 1970. Not long after they sold that farm property, several family members, along with Dr. Tony Cedolini and friend Ernie Miller, began making wine in the basement of the DeRose family house, and they continued to do so until they launched their winery in Cienega Valley. Originally named Cienega Valley Winery, they renamed it DeRose Winery in 1993.

Pat, who had guided both the vineyard management and winemaking since the start, retired from the winery about five years ago. Al grew up at the vineyard estate, and he learned about growing the vines from his father. Al went on to earn an enology degree from Cal State University in Fresno in 2001. He’s taken the reins from Pat, and in addition to DeRose Winery, Al is the winemaker for Viña Los Chanchitos in Chile, allowing him to work harvests in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres each year. He makes his own Chilean wines under the Alchemy and Parróne labels and sells these at the DeRose tasting room as well as other wines they import from Argentina, Spain, Italy, and France.

DeRose Vineyard straddles the San Andreas Fault, and the site includes different soil types on either side. The eastern side has mostly granite and sandstone soil, with the higher portions to the west of the fault including granitic and calcareous soil. Al mentioned that there is a quarry for dolomite – a type of calcareous rock – very near the vineyard. The Cienega Valley climate is fairly warm during the growing season but winds from Monterey Bay typically start to cool it off considerably starting in the mid-afternoon. There are about 100 acres of vines, with around 40 acres dating from before 1900. Most of vines at DeRose are on hillside locations at over 1,100-foot elevation with varying slopes and orientations. The vines are dry-farmed, without irrigation, using organic methods – Al told us that the last time the vineyard had been irrigated was in 2000. The fruit typically retains good acidity due to the cool nighttime temperatures and the wind.

Al and Pat worked together in both the vineyard and winery for about 25 years before Pat’s retirement. They restored the old vineyard, which had not been well-tended in the years before they took over. A small block of the 1855 Négrette vines remains in the vineyard, while other plantings that are about 110-120 years old and are still in production include Zinfandel, Cabernet Pfeffer, more Négrette, and – surprisingly – Viognier. Al said that there are also some Alicante Bouchet and Rose of Peru vines interplanted in the older parts of the vineyard. More recent – but still 40+ year-old – plantings include Syrah and Cabernet Franc. Newer vines have largely been propagated from old-vine cuttings. Most of the fruit from their vineyard goes into the DeRose wines though they typically also sell about 5-10% to other vintners.

Along with his love of growing the vines and making wine, Pat DeRose enjoyed collecting and restoring old cars. A few of the winery’s bottlings are named for a specific automobile model and feature a photo of that car on the front label. We tasted one of these, the “Hollywood Red” blend named for the classic 1941 Graham Hollywood automobile. Other bottlings with classic auto labels include the “Sharknose Chardonnay” (named for another Graham model) and “Continental Cabernet.” Al told us that the “Hollywood Red” is their top seller, and is made in a solera-type of system going back to 1997. Each year they bottle half of the most recent vintage along with half that’s a blend of all the older vintages – the other half of the recent vintage is in turn blended with the older ones for use in the following years.

All of the DeRose wines are fermented with native yeast and are bottled unfined and unfiltered, with minimal intervention winemaking. Wines are aged in French oak, using a variety of coopers and up to around 15-20% new barrels. White and rosé wines are bottled under screwcap. Most of the wines are given additional aging in bottle prior to release, so the available vintages are generally bit older than found at many wineries.

Al started out our tasting with the 2020 Chardonnay, aged in French oak barrels for 10 months with lees-stirring but no malolactic fermentation, and then aged in bottle for another two years before release. This had apple and stone fruit aromas plus floral hints, with medium-light body and a lively texture. We followed that with the 2019 Viognier – this was sourced from old vines on limestone soil near the highest part of the vineyard, and barrel-fermented in neutral oak with no malolactic fermentation. With bright but subtle citrus, stone fruit, and floral aromas, it had fine acidity and a long, fresh finish. Next was the 2023 Zinfandel Rosé, fermented in neutral oak and then aged in stainless steel prior to bottling. Displaying strawberry and watermelon notes plus hints of fresh herbs and flowers, it had medium-light weight and a pleasant finish.

Our first red wine was the 2021 Cabernet Franc, from vines planted nearby the winery buildings. This had ripe plum and black cherry fruit with spice and dried herb notes in support, with a moderately rich texture and youthful tannins. Al next poured us the 2020 Négrette – the fruit for this bottling came from younger vines developed from the old Négrette vine cuttings. Featuring earthy plum and darker berry aromas along with a savory herbal element and undertones of spice and vanilla, this had medium body and a lively mouthfeel and finish.

We continued with the NV “Hollywood Red” #22, made using the solera system described above, is a blend of 65% Zinfandel, 15% Syrah, 10% Négrette, 4% Cabernet Pfeffer, 4% Rose of Peru, 1% Alicante Bouchet, and 1% Cabernet Franc, all from vines planted between 1855 and 1918. This definitely showed the Zin component upfront, with ripe black cherry and wild berry aromas, plus spice, earth, and a touch of pepper, with a moderately rich texture and fine tannins. We finished up our tasting with the 2007 Port, made from 100% Cabernet Franc. With ripe plummy fruit, spice, and vanilla aromas, this had a rich mouthfeel yet good acidity. On its own this shows a touch of a port-style wine’s alcoholic heat, but paired with food – chocolate would do well here! – it should be a fine accompaniment.

Al had to leave as we were finishing up our tasting – he was on his way to the winery’s recently-opened second tasting room in San Martin, between San Jose and Gilroy – and he left us in the capable hands of Luke Garrett, who works mainly in sales and at the tasting room for DeRose. We’d mentioned to Al and Luke that we were interested in seeing some of their old vines, and Luke led us out into the vineyard. The Cabernet Franc vines planted in 1985 were directly across from the winery buildings, and from there we followed Luke a short distance up the hillside to the old Zinfandel, Négrette, and Viognier vines. It’s always a treat to see old head-trained vines such as these, and it’s wonderful that the DeRose family was able to restore the vines after they’d been poorly managed by the previous vineyard owners.

In addition to the wines we tasted, DeRose also makes Carignane, Cabernet Pfeffer, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, Zinfandel, Sangiovese, plus a couple of additional red blends and Port-style wines. They currently produce about 5,000 cases per year. A new project for DeRose is a return of the Cienega Valley Winery label for a line of value-priced wines.

We had a great time at DeRose visiting with Al and Luke. They were both terrific hosts and made us all feel right at home at the winery and in the vineyard. I enjoyed all of the wines we tasted – many were on the fruit-forward and somewhat bolder side, though none of them were over-ripe or jammy at all, and the fine acidity that they displayed kept them all very well-balanced. My favorites included the 2019 Viognier, 2020 Négrette, and NV “Hollywood Red” #22. A visit to DeRose should certainly be on your itinerary if you’re exploring the wines of San Benito County. With their new San Martin tasting room you can now visit them very easily from the South Bay Area, though a visit to their Cienega Valley winery and vineyard will give you a great opportunity to discover an important part of California wine history.

Wes, Stephanie, Larry, and I had planned to have a late picnic lunch at DeRose after our tasting there, and we walked to a table at their shaded patio across from the winery. This was a pleasant place to relax and have our lunch. Though we were running a little late – seems that inevitably happens – we still had time for a nice break before moving on. At least it was a short drive, as our next stop was only about a half-mile up the road from DeRose.

Eden Rift Vineyards

Our final San Benito County wine visit of the day was at Eden Rift Vineyards, a very short drive from our previous stop. I’d tried a few Eden Rift wines in recent years that friends had brought to tastings and dinners, and enjoyed them. I was able to get in touch with winemaker Trevor Chlanda and he arranged for our group’s tasting at the winery. Wes, Stephanie, Larry and I walked into the tasting room, located in the historic Dickinson House – designed in 1906 by Frank Lloyd Wright associate Walter Burley Griffin – and we were greeted there by Hannah Harvey, who led us out onto the large patio for our tasting.

The Eden Rift property makes up part of the earliest commercial vineyard plantings in San Benito County. The first vines – possibly Mission – were planted around 1851 by Frenchman Theophile Vaché, who added French grape varieties not long afterwards, including one of California’s first plantings of Pinot Noir in about 1860. After William Palmtag purchased the property, he expanded the vineyard and winery in the 1880s, and subsequent owner John Dickinson expanded them further in the early 1900s. A bit later, the Valliant family headed up the vineyard and winery. In the 1950s, wine giant Almaden Vineyards bought the land, and later sold it to Heublein – a period when the vineyard was farmed more for quantity than quality and when many of the older vines were pulled out and the site planted with other grape varieties.

The single large property was split into two not long afterwards, with part of it going to the DeRose family (now DeRose Winery), while the other part, purchased by the Gimelli family, became Pietra Santa Winery – this is the portion that is now Eden Rift. Many of the vines were replaced with Merlot, Sangiovese, and Dolcetto during the Pietra Santa years, though some older vines including a small block of Zinfandel were preserved. The Pietra Santa property was purchased in 2016 by Christian Pillsbury – a longtime California wine business veteran – who changed the name to Eden Rift as a tribute to both John Steinbeck’s “East of Eden” and the San Andreas Fault zone that runs through the estate.

Pillsbury had been looking at older vineyard properties in a number of California wine regions, with a goal of buying one to preserve it and restore it to its historical roots, and as soon as he saw this one he knew it was what he wanted. Soon after he purchased the site, he and original Eden Rift winemaker Cory Waller began the process of replacing most of the plantings there with Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and Pinot Gris – a return to the vision of original owner Theophile Vaché. The soil and climate of the vineyard is similar to that of famed Calera Wine Company, located just a couple of miles away, so Pillsbury was confident that these grape varieties would do well at the site.

There are currently about 117 acres of grapevines planted at Eden Rift. About 90 acres is planted to Pinot Noir, including Dijon clones 115, 667, 777 and 828, Pommard 4, and California heritage clones Mount Eden, Swan, and Calera. These vines are planted on some of the site’s distinctive terraces, as well in specific blocks including the Lansdale and Palmtag blocks. Over 22 acres of Chardonnay are planted – also some on the terraces – plus a little over 3 acres of Pinot Gris, which is planted entirely on the terraced part of the site. There are also small blocks of Grenache, Syrah and Mourvèdre planted in the vineyard. In addition to these more recent plantings, the small (less than one acre) own-rooted, head-trained Dickinson Block of 1906 Zinfandel is still there. Eden Rift uses most of the estate fruit for their own wines but they do currently sell about 10-20% each year to other producers.

There’s about a 400-foot elevation difference between the top and bottom portions of the vineyard, and various slopes and aspects. The vineyard soil includes decomposed granite, limestone, and dolomite, and Pillsbury had 36 soil pits dug in order to help determine what to plant in various parts of the vineyard and what rootstocks to use. The vines are farmed using mostly organic methods. The daytime climate at the site is warm during the growing season but it cools off considerably at night, and my friends and I couldn’t help but notice the cool mid-afternoon breeze as we sat on the patio outside of the Dickinson House.

Although winemaker Trevor Chlanda wasn’t able to meet with us during our visit, we had several text and email exchanges that helped me better understand the property and the wines. Trevor, who took over the winemaking at Eden Rift in the summer of 2024, worked at several noted Napa Valley producers as well as Duck Pond Cellars in Willamette Valley and Williams Selyem Winery in Russian River Valley – both well-known for their Chardonnay and Pinot Noir bottlings.

Winemaking at Eden Rift is minimal intervention, with fruit picked at night to ensure that it’s cold when it reaches the winery. All of the fruit is fermented with native yeast. Chardonnay is whole-cluster pressed, fermented in French oak, and aged in barrel for 10-11 months, going entirely through malolactic fermentation. Pinot Noir fruit is fermented with a percentage of whole clusters, ranging from about 20-30% for the Estate bottling and up to 100% for some of the more limited bottlings. The Estate Pinot is in French oak for about 10-11 months while other Pinot bottlings receive up to 16 months of barrel age before bottling. Wine for the estate bottlings of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir is aged in about 15-20% new French oak barrels, while other bottlings get up to 35% new oak. They’re moving toward aging in puncheons rather than barriques with white wines, for gentler oak extraction. Other red varieties have been aged in a little new oak in past vintages but Trevor said that they’re moving to older barrels for these, plus some once-used barrels for Zin and Syrah.

Hannah at the tasting room poured the winery’s current tasting flight of wines for Wes, Stephanie, Larry, and me as we sat out on the pleasant patio. We could see a sizable brick building with a distinctive tower across the vineyard from Dickinson House – it looks old but we learned that it was built only about 25 years ago, when the property was Pietra Santa, and is the winery building. We also got a look at the 1906 block of Zinfandel vines, which are right next to the patio.

We started our tasting with the 2023 Estate Rosé. The Pinot Noir fruit that goes into this is from fruit that’s farmed, picked, and made specifically for rosé wine – it’s whole-cluster pressed and then fermented and aged entirely in stainless steel, with no malolactic fermentation. This had subtle floral red fruit and tropical fruit aromas, with a medium-light mouthfeel and lively finish. Our next wine was the 2022 Valliant Griva Vineyard Sauvignon Blanc. The Valliant line of Eden Rift wines is from non-estate fruit. This Musqué clone Sauvignon Blanc was sourced from the Arroyo Seco region of Monterey County, whole-cluster pressed, and made in both stainless steel tanks and neutral French oak, with no malolactic fermentation. With herbal grapefruit and stone fruit plus floral undertones, it had a pleasant texture and finish. Hannah continued our tasting with the 2021 Estate Chardonnay, which was aged in both older and new French oak for 11 months and went completely through malolactic fermentation. Displaying stone fruit and tropical fruit notes along with spice, oak, and hints of flowers, this was medium-bodied with a long finish.

We proceeded to the 2021 Estate Pinot Noir, made mostly from 115, 828, and 777 Pinot clones. This had about 25% whole-cluster fermentation, and was aged in around 30% new French oak. This had ripe black cherry and plum aromas along with spice and a touch of earth, with medium-light body and milder tannins. The last wine that Hannah poured for us was the 2020 Lansdale Pinot Noir. This came from Calera clone Pinot grown at the highest part of the vineyard (Q-Block, at around 1,600-foot elevation), and fermented entirely with whole clusters. I thought this wine showed more character than the previous one, with black and red cherry fruit, flowers, a savory herbal component, and undertones of spice and oak, with more texture on the palate, fine acidity, and good structure for continued development in the cellar.

Since Trevor wasn’t available when my friends and I visited Eden Rift, we weren’t able to taste all of the wines that he’d wanted us to, but he generously sent three additional bottles to try afterwards. All three are limited-production bottlings, and Trevor felt that they would really showcase some of the vineyard’s most special fruit. I was able to get together again with Wes, Stephanie, and Larry a few weeks after our winery visit to taste these wines. The 2022 Terraces Chardonnay was made from entirely from the terraced Chardonnay vineyard block, with clones 76 and 4. Whole-cluster pressed, it was aged for about 10 months in neutral and new French oak. It was a little reductive at first, but with some air this featured subtle lemon and pear, fresh herbs, a light touch of oak, and a stony mineral note, medium bodied with vibrant acidity and a fresh finish.

Trevor also sent the 2022 Terraces Pinot Noir, sourced from two terraced vineyard blocks. This was entirely whole-cluster fermented, and then aged in French oak barrels (22% new) for 16 months. Showing black cherry fruit, savory herbs, and lots of spice, this had great structure and a lively finish. Quite promising but it still seems young and can use some time in the cellar for all of the components to really mesh. Rounding out the additional wines that Trevor sent was the 2021 Dickinson Block Zinfandel. Fruit from these low-yielding Zin vines was destemmed, and the wine was barrel-aged for 14 months in both neutral and new French oak. This had ripe berry fruit, spice, and undertones of vanilla, with a broad mouthfeel and long finish.

Other releases include Terraces Pinot Gris, Reserve Chardonnay, Palmtag Pinot Noir (entirely Mount Eden clone), and a few limited-production wines including Syrah and Valliant Petite Sirah. Total annual production for both the Eden Rift and Valliant labels is currently around 10-12,000 cases. A new development at Eden Rift is a Blanc de Noirs sparkling wine that will be released a few years from now.

Our visit to Eden Rift was a very pleasant and relaxing experience, and Hannah was a friendly and knowledgeable server for us. I have to thank Trevor again for sending those three additional bottles that he’d wanted us to taste, as they really gave us a better picture of what the vineyard is capable of producing. All of the wines were very well-balanced, and I don’t believe any of them other than the Zinfandel were over 14% alcohol. While all of the wines were good, I thought the 2022 Terraces Chardonnay, 2020 Lansdale Pinot Noir, and 2022 Terraces Pinot Noir were a noticeable step up from the others, and they were my three favorites, and the 2021 Dickinson Block Zinfandel was a fine expression of old-vine Zin. These wines were standouts and definitely worth seeking out. For its long history, its relaxing atmosphere in a beautiful setting, and its wines, a visit to Eden Rift is certainly recommended if you’re visiting the Cienega Valley wine region.

I had a great time visiting Popelouchum Vineyard, DeRose Winery, and Eden Rift Vineyards in San Benito County. Together with my visits to explore San Benito wines last year, I now have a much better understanding of the region’s long wine history as well as the broad range of fine wines coming from there. Though they’re following different paths, DeRose and Eden Rift in Cienega Valley share a common history, each continuing to grow grapes and make wine from parts of the region’s earliest commercial winegrape vineyard, helping to preserve part of California’s wine heritage. And while those two wineries celebrate the past in their current work, Randall Grahm at Popelouchum Vineyard is looking to create a new future for California wine with his fascinating grapegrowing projects there. I really enjoyed my “off the beaten path” wine visits to San Benito County, and I may well head back there again. As always, thanks to everyone that I visited for being so generous with their time and their wine!

|